Women ruled the Celts of Britain: researchers have discovered new evidence (photo).

It appears that women played a significantly more substantial role in the lives of the ancient Celts than previously thought. At least, new excavations are shedding light on the life of the Durotriges tribe, who lived in what is now modern-day Britain from around 100 BC to 100 AD.

A new study was published in the journal Nature on January 15. It focuses on describing the traditions of the Dorset population (southern England) during the Iron Age.

Researchers analyzed 57 remains from Durotriges burials to trace familial relationships and migration waves of people to the British Isles. This tribe had a tradition of burying their dead in an embryonic position, which sets them apart from others.

The most remarkable finding was that members of this tribe seemingly practiced matrilineal (i.e., through the female line) marriage traditions. In other words, the mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down exclusively through the female line, showed very low diversity. This indicates that all women in a specific region were descendants of one distant ancestor. Conversely, men appeared to be migrants who brought their DNA from other settlements.

"This was a cemetery of a large kin group. We reconstructed a family tree with numerous branches and found that most members traced their maternal line back to one woman who lived centuries ago. In contrast, paternal connections were nearly absent," said study author Lara Cassidy, an assistant professor in the Department of Genetics at Trinity.

She emphasized that this is "the first case where such a system has been documented in prehistoric Europe," and it aligns with how the Romans described the Celtic population of Britain.

Following this, researchers examined remains from Celtic settlements in other parts of Britain and found a similar trend of a large number of descendants from one woman residing in a single region.

In addition to archaeological findings, scientists also rely on Greek and Roman records from that era. However, these accounts are not always highly accurate, leading to a degree of skepticism regarding the information they contain. Nonetheless, in this case, it seems that the Romans' astonished records about local queens leading armies may indeed be quite truthful.

"It was assumed that the Romans exaggerated the freedoms of British women to portray a picture of a wild society," the scientists state.

The new study suggests that these societies were much more organized, as they had a clear understanding of their ancestry and married into distant branches of their kin, avoiding close kinship ties. The hypothesis of influential Celtic women is also supported by the discovery of rich inventories in many female graves.

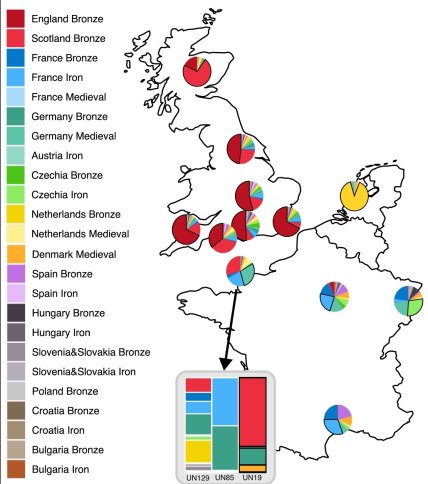

The research also illuminated other previously unknown aspects. For example, it was found that a greater genetic diversity among men was observed along the southern coast of Britain. This may be linked to more frequent migration waves from continental Europe.

In contrast, northern regions exhibited greater genetic isolation, which may indicate that the ancestors of these people had lived there since the Bronze Age.

As previously reported, a burial site was discovered in Hungary containing the remains of a woman with weapons. Archaeologists speculate that she may have been involved in military affairs.